Seoul, the capital of South Korea, is the country’s largest metropolis, boasting huge skyscrapers, high-speed public transportation and the latest in trends that will soon circle the globe. But this city also holds hundreds of years of history, culture and religion, which have shaped its growth and continue to impact how it functions today and thus how it will work in the future. The geography of the Seoul area is just as varied as its history; director Brandon Li explores the different aspects of the city through captivating shots of the landscape that are juxtaposed with similar-looking modern features. Above all, this video focuses on the residents of Seoul—their daily lives, journeys, work and commutes—to tell a story about the city.

Tibetan Worship and Culture at Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple

Take a visual visit to Jokhang Temple in Tibet, one of the holiest destinations for Tibetan Buddhists, with this magnificent photo essay by Carol Foote. See traditional dress and culture on this pilgrimage route.

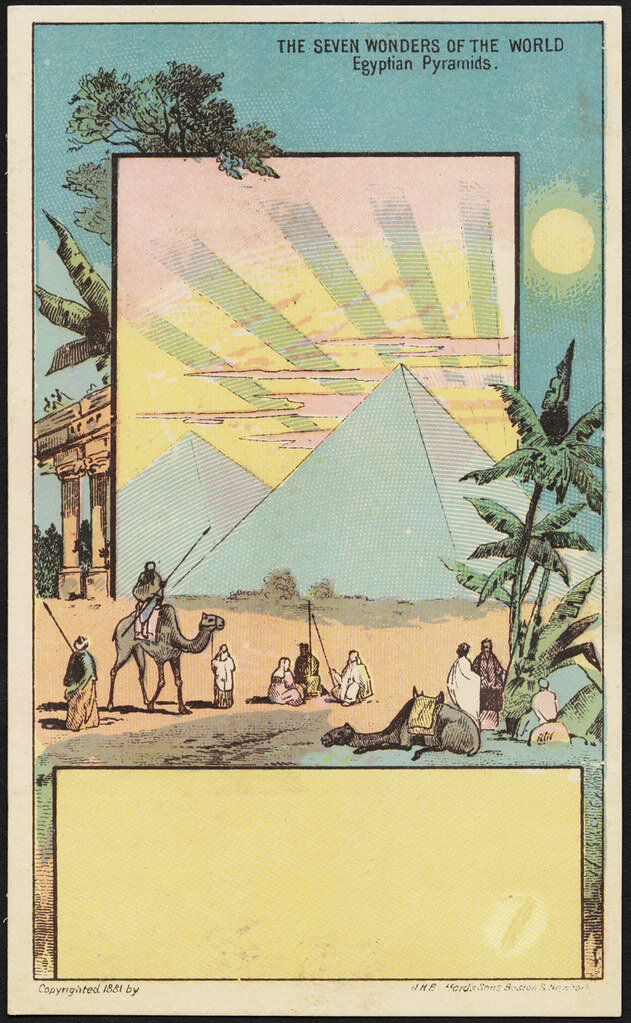

Read More6 Interesting Facts about the Egyptian Pyramids

There is still so much we don’t know about the history and structure of the Egyptian pyramids. Here are six things that you may not have known about the pyramids and ancient Egypt.

Egyptian pyramids in the sunset. Club Med UK. CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Egyptian pyramids are famous for their buried mummies and treasures, but there are still many secrets waiting to be uncovered about their history. Take a deep look into the ancient pyramids’ past with these six interesting facts.

The seven wonders of the world, Egyptian pyramids. Boston Public Library. CC BY 2.0.

1. Once upon a time, they sparkled.

According to research on ancient texts and found evidence, it is thought that the Great Pyramid of Giza used to shine like glass and sparkle in the sunlight. Ancient Egyptians even called the pyramid “Ikhet,” which translates to “glorious light.” This is mainly because the pyramid was originally covered in polished limestone which reflected light like a mirror and made the pyramids visible from anywhere nearby. What is even more interesting is that the speed of light—299,792,458 m/s—are also the exact coordinates of the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is at 29.9792 degrees north, 31.1342 degrees east. Spooky? Definitely.

Entering the pyramid. Trey Ratcliff. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

2. Many of them were robbed.

A lot of the unknown history of the pyramids can be blamed on tomb robbers. Tomb robbing was a serious problem in ancient Egypt because robbers targeted the tombs for looting—even Kings’ tombs were broken into. It was the Egyptian belief that everything buried with you was taken into the afterlife, so Kings and Queens were buried with unimaginable amounts of riches. It was also very common for people to steal from their ancestors’ tombs —some even dumped the body and stole the sarcophagus. Egypt was a cashless society until the Persians came in 525 BCE, so those who stole from the tombs would have had to trade their stolen goods to higher, corrupt officials. Those caught would be executed for the offense.

The Great Pyramid of Cheops. Boston Public Library. CC BY 2.0.

3. We still don’t know how they were built.

Although the pyramids are over 4,000 years old, professionals still don’t understand how the ancient Egyptians managed to build the pyramids without advanced technology. The most accepted theory is that they used ramps to bring materials to the top, which has been proven by a recent discovery. Researchers in Egypt discovered a 4,500-year-old ramp used to haul alabaster stones out of a quarry. The ramp system dates back to Pharaoh Khufu, who built the Great Pyramid of Giza. However, the way in which the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids is still a mystery because the pyramids were not made of alabaster, which is what the discovered ramp helped to move.

Khufu’s Great Pyramid. Bernt Rostad. CC BY 2.0.

4. There is a secret chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza (Khufu’s Pyramid).

Weighing in at 5,750,000 tons, the Great Pyramid is simply a feat of architecture. To add further to the mystery, a previously unidentified chamber in the Great Pyramid was discovered in 2017 when physicists used the by-products of cosmic rays to reveal an at least 100-foot long void. The mysterious space’s dimensions are similar to the pyramid’s Grand Gallery, which is the corridor that leads to the burial chamber of Pharaoh Khufu. What lies within the space is still unknown, as well as its purpose. Scientists hope to find out more about this newly discovered area and what it was used for.

Tomb of Perneb, carving of offering bearers. Peter Roan. CC BY-NC 2.0.

5. It was tradition for the living to share food with the dead.

Ancient Egyptians believed that tombs were eternal homes for the mummified bodies and the ka spirits that lived within them. Each tomb had a tomb-chapel where families and priests could visit the deceased and leave offerings for the ka, while a hidden burial chamber protected the mummified bodies from potential harm. Visitors offered food and drink to the dead daily, and once the offerings were consumed by the ka, the living were free to eat and drink their offerings. The Beautiful Feast of the Valley was an annual festival of death and renewal where families spent the night in the tomb with their ancestors and feasted with them in celebration of their lives.

A statue ofNefertiti in the Altes Museum in Berlin. George M. Groutas. CC BY 2.0.

6. Egyptian women and men had equal rights.

In ancient Egyptian times, men and women of the same social class were treated as equals in the eyes of the law. Women could sell, own, earn, buy and inherit property. If widowed or divorced, women could raise their own children. Women could also bring cases before a court. Overall, women could legally act on their own and were responsible for their own actions. Although everyone in ancient Egypt was expected to marry, wives still had an important, equal and independent role in their marriage.

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

Siberia's Lake Baikal, One of the Deepest Lakes in the World

Recognized as one of the few remaining ancient lakes in the world, Lake Baikal has preserved natural history and housed thousands of animal species for centuries.

Lake Baikal surrounded by greenery. Markus Winkler. Unsplash.

In Siberia, just north of the Mongolian border, sits Lake Baikal, one of the deepest lakes in the world. The lake houses 22 percent of our planet's fresh water and measures over 5,300 feet deep. Furthermore, its location between mountains allows for over 330 rivers and streams to connect to it, and the lake is made up of three basins. While Lake Baikal only equates to around half the surface area of Lake Michigan, measuring in at about 12,200 square miles, its magnificence lies in its history.

Experts have estimated that the lake is between 25 and 30 million years old, making it one of the few remaining ancient lakes on the planet. This is because it lies in an active rift zone due to its plate tectonics, unlike most other lakes which have a history of being covered by ice sheets in previous glacial periods. Most ancient lakes are formed when the Earth's plates begin to move apart from each other, creating a rift valley that is deepened over time by erosion. Eventually, the rift widens so much that it begins to fill with fresh water. Around 75 percent of Earth's ancient lakes have been formed through this process, with the exceptions having been formed by meteor impacts and volcanic action.

Therefore, not only does Lake Baikal preserve years of Earth's history, but it is exclusively home to around 2,000 unique animal species. Although the lake is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, that hasn’t stopped climate change from affecting the lake, as the surface temperature has increased by 1.5 degrees Celsius over the past 50 years. In conjunction with increasing chemical pollution, the ecosystem is believed to be rapidly changing for the first time in decades.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, locals have been taking advantage of the lack of visitors populating the lake, many beginning to trek out to visit the body of water themselves. Especially during the fall and winter months, many visitors enjoy skating, hiking, or even skiing over the ice and snow.

Ice formed over Lake Baikal. Daniel Born. Unsplash.

Located near one of Russia's largest cities, there has been a constant tug-of-war between developers, locals and environmentalists to seek a balance between encouraging tourism which benefits the local economy, and protecting the deteriorating ecosystem. While the momentary break in visitors has undoubtedly allowed the ecosystem to begin to recover, ultimately its fate lies in the hands of its visitors.

RELATED CONTENT:

PODCAST: Traveling with the Nenet Reindeer Herders in the Siberian Arctic with Patrick Barrow

VIDEO: A Diamond Mine in the Rough

Zara Irshad

Zara is a third year Communication student at the University of California, San Diego. Her passion for journalism comes from her love of storytelling and desire to learn about others. In addition to writing at CATALYST, she is an Opinion Writer for the UCSD Guardian, which allows her to incorporate various perspectives into her work.

Islamic Architecture in Spain

While many can forget that Arab and North African Muslims controlled parts of Spain for almost 800 years, longstanding Spanish architecture is a testament to the Muslim reign. Arabesque patterns, Islamic motifs and sandy colors have been preserved in some of Andalusia’s most famous palaces and fortresses.

Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain. Richard Mortel. CC BY 2.0.

Arab and North African Muslims conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century. Ruling for almost 800 years in Al-Andalus (currently Andalusia), Muslims inevitably left traces of their presence in the region. Everything from language and religion to architecture and art was adopted by Spain during the Muslim reign. Around 4,000 Spanish words which are still in use today originated from Arabic. The majority of these words are nouns related to food, animals, nature and science. For example, the Spanish word for “olive” is “aceituna” and is derived from the Arabic word “zaytünah.”

While aspects of the Arabic language can be found in Spanish, Islamic architecture is the true evidence of the Arab and North African Muslim reign in Spain. Certain sites in modern-day Andalusia make you feel like you’re in Morocco or Syria. Today, Islamic architecture is most prevalent in Cordoba, Seville and Granada—Spanish cities in Andalusia—with their palaces and holy sites.

Cordoba

Desert colored walls in the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Waqqas Akhtar. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Cordoba was the capital of Al-Andalus when it was first conquered in 711 A.D. The Great Mosque of Cordoba is a testament to the Arabic and Islamic influence in the city. Elaborate building programs and agricultural projects were sponsored by Prince Abd al-Rahman I from Damascus, Syria. The prince imported plants from Damascus, some of which still stand in the yard of the Mosque of Cordoba today.

Previously operating as a mosque and church at different points in history, the captivating structure includes a hypostyle prayer hall, a beautiful courtyard with an extravagant fountain, a colorful orange grove, a walkway circling the courtyard and a minaret which is now a bell tower. Islamic calligraphy and verses from religious scriptures fill the sandy, red and white colored columns. Geometric shapes dominate the structure—in everything from design to entryways. One major Islamic motif that is evident in this structure is the horseshoe shaped “mihrab.” The mihrab identifies the wall that faces Mecca—Islam’s holiest city that features the home of God, the Kaa’ba—and indicates which direction to face while praying. The mihrab is decorated in gold and brown detailing. Above the mihrab sits a mesmerizing dome filled with pointed gold arches and radial patterns fill the ceiling.

The dome above the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordoba. mitopencourseware. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Seville

The Royal Alcazar in Seville is one of the world’s oldest palaces that is still in use today. This palace has been awarded status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Alcazar was first built in the 11th century when the Arabs moved in and sought to create a secure, residential fortress. Since then, Alcazar has been home to the many monarchs who have taken control of Seville. The initially Islamic structure was renovated by its following rulers; however, the palace’s Islamic roots shine through as many of its Islamic components have been preserved.

One of the palace’s courtyards, the Patio del Yeso, was created in the 12th century when the region was still under Muslim control. The courtyard features a large pool in the middle—a common theme in Islamic architecture. Water is at the heart of Islamic architecture for both practical and spiritual reasons. Considering that the Arabs and North Africans came from dry climates and desert landscapes, it was important for them to have easy access to reliable sources of water. Furthermore, in Islam, water symbolizes life and purity. Water in gardens, specifically, symbolizes the sacred lake in paradise that is reserved for only the righteous.

Other recurring Islamic motifs that are found in the Alcazar include keyhole or horseshoe shaped arches, doors and windows; traditional Islamic plasterwork and latticework; Islamic writings; and a heavy presence of plants. The horseshoe arch is known as an “alfiz” and the Islamic-style window screens are known as “mashrabiya.” These, in addition to the icicle-like droppings from ceilings and domes, are common components of modern-day mosques and other traditional Islamic structures.

The gardens of the Alcazar were used not only for aesthetic purposes, but also for functional purposes. While the plants and trees were grown in the palace’s gardens for beauty, the plants were also used to feed members of the court. The gardens themselves were strategically structured to resemble what Muslims imagined paradise to look like based on the descriptions in the Quran.

Garden in the Royal Alcazar, Seville. Jocelyn Erskine-Kellie. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Granada

Alhambra Palace Fortress in Granada, Spain. Victor Wong. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The Alhambra Palace in Granada is further evidence of the Islamic rule in Spain. The name Alhambra itself derives from the Arabic word “Al-Hamra” which means “red.” The palace was given this name for its reddish bricks and walls which can be seen from afar. Alhambra’s layout mimics that of many other palaces for Muslim princes. Three main floor plans dominate the site: the “mexuar” was open to all and the room where sultans received their subjects, the “diwan” is the throne room where receptions were held, and the “harem” is the prince's private quarters. Islamic inscriptions and verses from the Quran flood the walls, while the gold detailing accents the writings.

Mosaics and colored tiles in geometric and plant-like shapes, referred to as “alicatado,” are also in certain quarters. The mosaics are not only decorative but also contain strategically chosen tiles to cool the structure in the summertime. Plant motifs align with Islamic principles, as the depiction of human images is often frowned upon. The Fountain of the Lions in Alhambra is one of the most photographed features of the palace, with 12 lions spewing water in the middle of the courtyard. Other famous aspects of Alhambra which are covered in arabesque patterns and constructed to resemble the gardens in heaven, include the Generalife and El Partal, two of the quieter locations in the palace.

Keyhole shaped windows with arabesque patterns in Alhambra. Güldem Üstün. CC BY 2.0.

Fountain of the Lions in Alhambra. Alexandra Stevenson. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Geometric mosaics in Alhambra. Víctor. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

RELATED CONTENT:

Mia Khatib

Mia is a rising senior at Boston University majoring in journalism and minoring in international relations. As a Palestinian-American, Mia is passionate about amplifying the voices of marginalized communities and is interested in investigative and data-driven journalism. She hopes to start out as a breaking news reporter and one day earn a position as editor of a major publication..

VIDEO: A Diary of Senegal

In a departure from typical travelogues, this video shows a unique picture of Senegal through glimpses into everyday rural life with a focus on the children growing up in this beautiful country. Each clip showcases the diversity in landscape, culture, and lifestyle Senegal’s people experience—all bound together by an enthusiasm for life. After watching this video, you’ll want to dance with the people on screen.

5 of the World’s Most Dangerous Hiking Trails

Everyone loves a good hike, but some trails around the globe stand out due to the intense challenges that they provide. The following five hikes should not be attempted by novice hikers.

Aonach Eagach, Scotland. Andrew Marshall. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Hiking can test our physical and mental limits, and is a powerful cardio workout that is proven to boost your mood. While it can be fun to test yourself and get your adrenaline flowing and blood pumping, there are some hikes around the world that can cause serious injuries if you are not careful.

These five hiking trails are not for the faint-hearted and should not be attempted by novice hikers.

El Caminito del Rey, Spain. Arthur Harrow. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

1. El Caminito del Rey, Spain — 4.8 miles

The name of this hike translates to “The King’s Little Pathway,” and it once was one of the world’s most hazardous footpaths. This aerial path is suspended 100 meters high against the walls of a gorge,. It was originally built from 1901 to 1905 between the waterfalls of Gaitanejo and El Chorro to move materials and workers to the local hydroelectric dam. The trail is named “The King’s Little Pathway” because, in 1921, King Alfonso XIII opened it to visitors and traveled along the walkway to the Conde de Guadalhorce dam.

The Caminito del Rey route runs through cliffs, canyons and large valleys. The area is inhabited by a wide variety of plant and animal species, such as Egyptian vultures, griffon vultures, golden eagles and wild boar. The path takes about three to four hours to walk, starting in the town of Ardales and ending in Álora.

The path closed to hikers in 2001 when five people fell to their demise into the river below. Fences were since built into the renovated path and it reopened in 2015.

Cascade Saddle. Tom@Where. CC BY-NC 2.0.

2. Cascade Saddle Route, New Zealand — 29.9 miles

This trek takes almost two days, or four to five days if you choose the expert route. Built in 1939 and located in the Matukituki Valley area and Mount Aspiring National Park in the Otago region, the route travels through scenery featured in the Lord of the Rings films, so many visitors flock to this route for photo opportunities.

The Cascade Saddle route is an alpine crossing recommended for experienced trampers. It is also recommended to hike it only in good weather during the summer. The Department of Conservation advises hikers to begin from the Matukituki side of the route, since ascending is much safer than descending. There are various different routes to take from there.

However, this route can be very dangerous in some parts, where the ground is slippery and unstable—especially when it is raining. Furthermore, there is danger of avalanches from June to November. Check the New Zealand Avalanche Advisory website before you go.

Several hikers have been injured on this trek, and some have even died. If you go, be sure to have the right skills and experience to make the decisions best for you along the trek—you must also bring the proper equipment.

Aonach Eagach ridge. mr__fox. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

3. Aonach Eagach, Scotland — 6 miles

Located near Kinlochleven in the Scottish Highlands, the Aonach Eagach trail features beautiful wildflowers and mountainous scenery. However, it is also a hard, exposed scrambling ridge between Am Bodach and Stob Coire Lèith. Getting to the summit requires endurance, hard work and lots of climbing. The ridge is 3,126 feet high, making this trail one of the U.K.’s toughest ridge walks.

The trail is only recommended for very experienced hikers in good weather conditions. The rocks can get very slippery in rainy conditions, and side paths are often extremely hazardous and difficult to return from. Over the last 10 years, there have unfortunately been many deaths on the trail, the most recent being in 2017.

The trail is best done east to west, and those who push through the experience are rewarded with the view of a lifetime.

Backpacking in Utah. Zach Dischner. CC BY 2.0.

4. The Maze, Utah, USA — 2.9 miles

Although short, trails in the Maze are ancient and lead into various different canyons. Located near Gunlock, Utah, the Maze Overlook Trail requires basic climbing skills in order to navigate steep portions of rock. A 25-foot length of rope also comes in handy to raise or lower packs in difficult spots.

The Maze sees only 2,000 hikers per year since it is so remote and is the least accessible hike in the Canyonlands. The best time to go is in the spring, when temperatures are lower.

The Maze is quite literally a maze of intertwined canyons and dead-ends. The routes do not have beaten trails and they often weave up and over canyons, which are extremely difficult to traverse. Water sources in the Maze are also very limited. Part of the danger comes from how it can take rescuers up to three days to reach hikers because the path is so remote.

The highlight of this difficult and remote path is the view. Hikers will be able to see the Colorado River and Green River converge from atop a massive desert rock in a breathtaking view. Visitors can also see petroglyphs (prehistoric rock carvings) from ancient human history.

Mount Huashan. Jinjian Liang. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

5.Mount Huashan, China — 12.2 miles

Located near Huayin in the Shaanxi province of China, Mount Huashan trails are not very trafficked due to their narrow peaks and dangerous, steep paths. However, the trails feature beautiful wildflowers and scenery, as well as built-in steps and light poles.

Mount Huashan is known to be one of China’s five sacred mountains and one of the most popular pilgrimage sites for Chinese people. It is also considered by many to be the original place of Chinese civilization and is praised as the “Root of Huaxia (China).” The famous plank walk is 7,070 feet high and located on the mountain’s highest peak. There are many different trails to follow in the mountain, but the Changkong Plank Trail is the most dangerous and thrilling. The 700-year-old trail is only 12 inches wide.

The first few miles of the trail are a gradual ascent until Thousand Foot Narrow, and then the trail becomes narrow and steep toward the North Peak. There are many places to stop to experience breathtaking sunrises or sunsets and mountainous scenery. This trail is meant for only very experienced hikers.

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

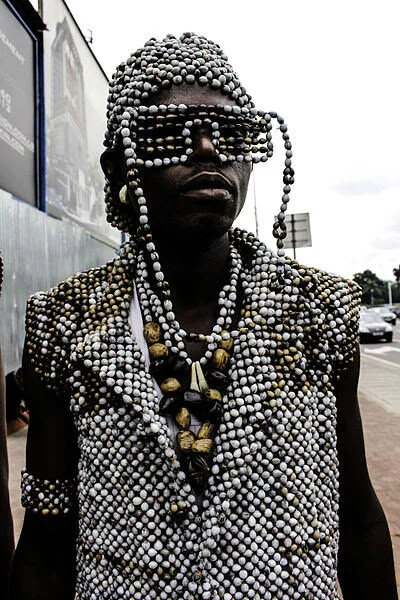

Congo Couture: “Sapeurs” Bring Europe’s Designer Fashion to Central Africa

The Republic of the Congo’s world-famous fashionistas strut through the streets of Brazzaville wearing outfits from Europe’s most revered designers. But to sapeurs, their fashion savvy is not just style but a lifestyle.

A sapeur in his Sunday best. ilja smets. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Maxime Pivot makes all the ladies scream. Men call him the pride of the town. Children follow him wherever he goes. The Republic of the Congo has never seen a more dashing, debonair, sharp-dressing gentleman. As a modern-day dandy in the streets of Brazzaville, he is a painterly splash of Congo couture amid near-universal penury. He boasts a double-breasted red suit, a pearl-white shirt, pitch-black sunglasses and a pink bowtie, an outfit to amaze the prim and plebeian alike. Rather than envy, his panache inspires pride. Some may call his focus on fashion amid staggering poverty vain, but really, he is preserving a decades-long tradition. He is a sapeur.

That means that he is a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—La Sape for short. In English, it translates to the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Every weekend, he and his fellow dandies meet to compare outfits from the hottest European designers, trade notes on color combinations and revel in the pomp of haute couture. They smoke, they dance and they conversate. They escape the squalor in which so many Congolese live—when sapeurs dress up, they feel like the richest men in the world.

No, they are not rich. Quite the opposite. By day, sapeurs are chefs, mechanics, electricians, craftsmen, businessmen, handymen, journeymen, or any other kind of blue-collar worker. 70 percent of people in the Republic of the Congo live in poverty, and most sapeurs are included in that number. What distinguishes them is not wealth but aesthetic distinction, good taste, and a deep knowledge of the latest fashion trends. They aspire to look like a million bucks, not spend it.

The street is a catwalk. Jean-Luc Dalembert. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The tradition began during the Congo’s colonial period. Congolese servants, tired of wearing their Belgian and French colonizers’ secondhand clothes, began saving their wages and purchasing the latest clothes for European dandies. After serving in the French army during World War II, Congolese soldiers returned home bringing closets-worth of European suits, shirts, ties, shoes and accessories. By the time the central African nation gained independence in 1960, many Congolese elites were making pilgrimages to Paris to rack up designer clothes for their wardrobes back home. Although they were accused of relying on white, “Western” traditions, most sapeurs insist on their artistic independence. As Papa Wemba, one of La Sape’s earliest celebrities, said, “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

However, investing in clothes instead of, say, property or livestock can be difficult to justify in one of the poorest parts of the world. Many sapeurs hide their expensive lifestyles from relatives to avoid endangering family ties. If a cousin learns that their family member would rather buy an Armani suit or Weston shoes than help put food on the table, they may feel betrayed and break off relations. Furthermore, the wives of sapeurs tend to bear the brunt of the sapeur lifestyle far more heavily than their husbands, as they suffer the financial cost without being able to revel in high fashion.

European style, African art. Opencooper. CC BY-SA 4.0.

La Sape is overwhelmingly male. Overwhelmingly, but not entirely. As the tradition evolves, more women are staking their claim as sapeuses. They, too, don designer suits from Versace, Dior and Yves Saint Laurent and develop mannerisms and gaits to build a persona around their clothes. Even children are beginning to partake in the sapeur culture. Many worry that Congolese tailors lack apprentices to carry on the tradition, so the sight of a child strutting down the streets of Brazzaville in an Armani suit assures them that the legacy of La Sape will continue.

In fact, Maxime Pivot established an organization, Sapeurs in Danger, to preserve the tradition of La Sape, which he asserts is not just about fashion but also is a way of life. When committing to the lifestyle, sapeurs adopt a code of conduct which Ben Mouchaka, another famous sapeur, summed up in 2000. He calls it the Ten Commandments of Sapeology.

1- Thou shalt practise La Sape on Earth with humans and in heaven with God thy creator.

2- Thou shalt bring to heel ngayas (non-connoisseurs), nbéndés (the ignorant), and tindongos (badmouthers) on land, under the earth, at sea and in the skies.

3- Thou shalt honour Sapeology wherever thou goest.

4- The ways of Sapeology are impenetrable for any Sapeologist who does not know the rule of 3: a trilogy of finished and unfinished colours.

5- Thou shalt not give in.

6- Thou shalt demonstrate stringent standards of hygiene in thy body and clothes.

7- Thou shalt not be tribalistic, nationalist, racist or discriminatory.

8- Thou shalt not be violent or insolent.

9- Thou shalt abide by the Sapelogists’ rules of civility and respect thy elders.

10- Through prayer and these 10 commandments, thou, as a Sapeologist, shall conquer the Sapeophobes.

Maxime Pivot aims to pass down the tradition of La Sape to any man, woman, or child willing to devote themselves to the lifestyle. He operates a school of La Sape where he teaches aspiring sapeurs how to combine colors tastefully and craft a swaggering gait. His classes teach that La Sape needn’t sap their wallets. As the sapeur life and style spread, he hopes that dandies will don local brands, not just expensive European ones.

Innovating a classic style. Makangarajustin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Then, La Sape could be truly independent from European designers. Fashion trends have been increasingly moving in that direction, thanks to Maxime Pivot’s efforts, especially now that La Sape has moved into the mainstream. Every August 15, the Republic of the Congo’s independence day, sapeurs march alongside the military, indigenous tribes and even the President in the largest parade of the year. Their flashy clothes and sauntering stride draw cheers from the crowd. Their tradition provides an example of how the country can emerge from an oppressive European past and spring into a liberated African future.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

Despite Economic Crisis, Lebanon's Landscape Stands Strong

Lebanon is in one of the world’s worst economic depressions since 1850; however, the nation continues to stand strong with its beautiful landscapes and soulful culture.

Lebanon—former French colony and home to the “Paris of the Middle East,” Beirut—has stood strong between nations riddled with tragedy. With Syria on its Northern and Eastern borders, Israel and Palestine on its Southern border and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Lebanon was frequently extending a helping hand to its war-torn neighbors. However, in recent years, Lebanon has plunged into a deep economic depression and is riddled with tragedy itself.

With 18 state-recognized religions in Lebanon, it is the most religiously diverse country in the Middle East. However, because religious leaders and political leaders are not mutually exclusive in the sectarian society, this diversity has led to public animosity toward the corrupt government. Although tensions have been brewing for years, the former government’s WhatsApp tax in late 2019 was the tipping point for Lebanese nationals and residents. Protests provoked by the tax broke out across the country and world, calling for a reformed Lebanese government.

Ambushed by the coronavirus a few months later, the Lebanese people experienced immense tragedy in 2020 when one of the world's largest non-nuclear explosions shook the Port of Beirut, leaving more than 200 dead and thousands injured. Lebanon is still haunted by the blast and is struggling to rebuild its destroyed neighborhoods amid COVID-19 and, according to the World Bank, one of the world’s worst financial crises in more than 150 years. To top it off, Lebanon has yet to create a new government since the government of Prime Minister Hassan Diab resigned due to public pressure following the explosion.

Currently, the U.S. State Department advises against traveling to Lebanon due to the large presence of COVID-19 in the nation, the threats of violence and the U.S. Embassy in Beirut’s limited ability to support U.S. citizens. Despite these warnings and Lebanon’s current crises, the people still hold their flag up high and are proud of the beautiful scenes and experiences their country has to offer.

Mountains, beaches, city lights—not only are all these scenic views found in Lebanon, but they are all less than an hour-long drive from one another. Lebanon’s landscape is especially unique because of the country’s small size. Residents and tourists alike can enjoy in a single day these three entirely different scenes and the activities associated with each of them.

There are two main mountain regions in Lebanon—Mount Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. Mount Lebanon extends across the entire country, while the Anti-Lebanon Mountains form the border between Lebanon and Syria, seeping more into Syrian territory. Snow-peaked year-round, Faraya, a village in the Keserwan District of the Mount Lebanon Governate, is one of the best ski spots in the country. Faraya, positioned at an elevation of 3,900 feet to 7,000 feet, is around 25 miles northeast from Beirut and around 23 miles southeast from Byblos, one of the oldest cities in Lebanon which sits on the Mediterranean coast.

“Miracle Monk of Lebanon,” Saint Charbel. DerekL. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Populated primarily by Maronite Christians, Faraya holds the largest statue and church of Saint Charbel in the world, standing 75 feet tall and around 30 feet wide. It is said that St. Charbel resided in this former monastery for over 20 years and those who visit and ask for assistance hear back. Since 1950, the “miraculous healings” of St. Charbel have been tallied and, as of mid-2019, the number lies above 29,000. Miracles were verified by priest witnesses before 1950; however, since 1950 and the advancement of medical technology, all “miracles” require medical proof for verification.

With Mount Lebanon paralleling the Mediterranean sea, the mountains are never too far away from the beaches. Along Lebanon’s coast lies hundreds of public and private beaches. One of the most famous public beaches in Lebanon is Joining Beach in the coastal city Batroun. With water so clear and blue it looks like it was dyed, Joining Beach is the perfect place to explore marine life. Underwater activities like snorkeling and scuba diving are common at this Lebanese shore.

Jeita Grotto. kcakduman. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Beyond swimming and sunbathing at the beach, Lebanon’s coastal towns show off wonders of nature. In Jeita Grotto, located 11 miles from the capital city in Jeita, exists a system of two interconnected caves that are around five and a half miles long. The upper galleries of Jeita Grotto is home to the world’s largest known stalactite—a mineral formation that hangs from the ceilings of caves—and was one of the top 14 finalists for the New 7 Wonders of Nature competition in 2011.

Beirut, Lebanon. marviikad. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Beirut, the heart of Lebanon, has its own natural wonders to show for as a big city in all its glory and flashing lights. Populated with restaurants, clubs and bars, Beirut’s nightlife is like none other in the Middle East. Alive all night, Lebanon’s pride and joy offers an experiential party scene. With clubs like Sunrise Beirut, partygoers start their outing as early as 10:30 p.m. and dance to techno until the sun lights up the sky. Mar Mikhael, named after the Maronite Catholic Church of Saint Michael, is a neighborhood in Beirut that is known for its aesthetic dining options—restaurants, cafes and bars are all fashionable outings in Mar Mikhael, the art hub of Beirut. Stationed on the marina, Zaitunay Bay is another classy area to shop, eat and be mesmerized by Beirut’s soulful city lights.

It’s true, Lebanon is still in crisis; however, the soul of the country lies within its people and landscape—both of which are beautiful, strong and resilient.

RELATED CONTENT:

PODCAST: Social Entrepreneurship in Lebanon

Mia Khatib

Mia is a rising senior at Boston University majoring in journalism and minoring in international relations. As a Palestinian-American, Mia is passionate about amplifying the voices of marginalized communities and is interested in investigative and data-driven journalism. She hopes to start out as a breaking news reporter and one day earn a position as editor of a major publication.

The Shamanistic Significance of the Mother Tree in Shaamar, Mongolia

This spiritual landmark represents the intersection between Buddhism and Shamanism within Mongolia.

Sunrise over a cluster of Yurts in Mongolia. Vince Gx. Unsplash.

The Mother Tree is a spiritual landmark located in Shaamar, Mongolia that holds deep significance to those who practice Shamanism. Also known as the Eej Mod, the tree is believed to act as a gateway between the human and spiritual worlds. Many make the trek to the tree in hopes of having their prayers answered.

Shamanism is a religious practice that is centered around a shaman, an individual believed to communicate with the souls of the dead and heal others. A large part of shamanistic practices revolve around one’s profound connection to the abstract and spiritual. Thus, the Mother Tree serves as a means to channel and amplify that energy.

While Buddhism is the most commonly practiced religion in Mongolia today, Shamanism is one of the oldest, and still holds deep cultural significance in modern times. Many of those who practice Shamanism believe that the Mother Tree became a gateway to the spiritual world after being struck by lightning. It is believed that the Mother Tree marks the intersection between modern Buddhism and traditional Shamanism, like many monuments and sites in Mongolia tend to do. Rather than ignore the past, Mongolian traditions preserve it.

Trees have a profound significance in the Shamanism tradition—Sacred Trees were often placed in the center of a Shaman’s house to allow their spirits to be freed from the body. This was believed to send a Shaman into a deep trance that would let them ascend in spirit flight, or spiritual ecstasy.

The original Mother Tree was surrounded by a yurt, and it was very common for visitors to leave incense sticks near the site. However, in 2015, one visitor lit an incense stick too close to the tree, causing it to catch fire. Only a stump of the original tree was salvaged. Today, this stump is still visited by many and covered in ceremonial blue scarves to signify honor and respect and is soaked with milk and vodka

Finding the Mother Tree is no easy feat; it is located off of a main road in Shaamar with nothing but a small sign that reads “Eej Mod” to guide visitors. The Tree is located a few kilometers along tracks which split from the main road, but most visitors end up traveling with locals to ensure that they find it. Every year, visitors from as far as Japan, Korea and China make the trek to the Mother Tree to experience its spiritual powers and have their prayers answered.

Zara Irshad

Zara is a third year Communication student at the University of California, San Diego. Her passion for journalism comes from her love of storytelling and desire to learn about others. In addition to writing at CATALYST, she is an Opinion Writer for the UCSD Guardian, which allows her to incorporate various perspectives into her work.

VIDEO: The World’s Longest Railway

Two continents, seven time zones, 9,288 kilometers. These are all features of the Trans-Siberian railway’s journey, which takes commuters from Moscow to Vladivostok, highlighting the diverse landscape and natural beauty of Asia. In this video, travelers spend 16 days on the railway, covering about 5,000 miles from Beijing to Moscow. Their route, deviating from the standard line, takes them — and viewers — through the Gobi Desert, along Lake Baikal, and into cities such as Kazan and Ulaanbaatar. This video highlights not only the underappreciated features of central Asia, but provides a sneak peak into the future of trans-continental travel.

Beyond Ice Cream, 7 Frozen Treats From Around the Globe

Ice cream is an ancient dessert, dating back to the second century B.C.. Since that time, countries around the world have developed their own versions of ice cream, from Indian kulfi to Ecuadorian Helado de paila.

Turkish dondurma is often served on a plate. tuhfe. CC BY 2.0

Ice cream is one of the most popular desserts in the United States. 6.4 billion pounds of ice cream were produced in the US in 2019 alone., The International Dairy Foods Association reports that, on average, each American consumes over 22 pounds of ice cream and other frozen desserts annually. But ice cream is not an American invention. The frozen dessert dates back to the second century B.C., when records show that leaders like Alexander the Great enjoyed ice and snow flavored with honey or nectar as a delicacy. Ice cream as we know it today likely derives from a recipe collected from the Far East by Italian explorer Marco Polo in the 16th century.

The ancient confection made from snow or ice flavored with honey, nectar, or fruit is present in historical records from around the world. While in England and America this treat evolved into the milk and cream based ice cream which we know today, other countries developed different versions of frozen desserts. Here are 7 frozen treats from around the globe, all impacted by the cultures that created them.

1. Dondurma, Turkey

Dondurma—the Turkish word for “freezing,” and sometimes referred to as Turkish ice cream—is often eaten with a knife and fork. Dondurma differs from American ice cream in several ways, the most obvious being the texture. While American ice cream is soft and creamy, dondurma is stretchy, chewy and does not melt easily, hence why it is most often served on a plate with a knife and fork. Dondurma is made from a milk and sugar base and added Arab gum, or mastic, a resin that gives the ice cream its chewiness. In addition to mastic, dondurma is thickened with salep, a flour made from the root of a purple orchid which grows in the mountains. The creation of dondurma is credited to the town of Kahramanmaraş, located at the foot of the Ahir Mountain in southern Turkey. The town has been producing dondurma for over 150 years, but the origins of the treat date back even further. Over 300 years ago, the people of the area mixed clean snow from the mountain with molasses and fruit extracts, creating an early form of ice cream. Today, dondurma is frequently served sprinkled with pistachios and can be found at restaurants as well as street vendors, where it is served in cones.

Colorful mochi ice cream. jpellgen (@1179_jp). CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

2. Mochi Ice Cream, Japan

Traditionally a dessert sold and eaten during the Japanese New Year, mochi has recently soared in popularity, especially in the United States. The term mochi refers to a unique Japanese delicacy dating back to 794 A.D., which is made from sticky rice dough. In Japan, mochi is most often enjoyed in small, round balls filled with red bean paste—a treat known as daifuku. In ancient times, mochi was made to be presented as an offering to the gods at temples and was also served to the Emperor and other nobility. Although mochi itself has been around for centuries, mochi ice cream was not developed until the 1980s. And, despite its Japanese roots, mochi ice cream is actually an American invention. It was created by Frances Hashimoto and her husband, Joel Friedman, who ran a Japanese-American bakery in Los Angeles during the 1980s. During a trip to Japan, the couple was inspired by the traditional daifuku to create their own mochi treat using ice cream. Today, mochi ice cream is sold at almost all major grocery stores and is available in a wide variety of flavors, like green tea, chocolate, mango and red bean.

Chocolate, Kesar, and Mango flavored kulfi. richardclyborne. CC BY 2.0

3. Kulfi, India

While often categorized as an Indian ice cream dish, kulfi is denser and creamier than ice cream, more closely resembling frozen custard. Kulfi is made from boiling milk until it solidifies, which is called khoa. Sugar is then added to the milk and the mixture is flavored as desired, typically using natural flavoring ingredients. Popular kulfi flavors include saffron, pistachio, mango, avocado and cardamom. After the kulfi mixture is flavored, it is poured into molds and frozen until the treat has set. Kulfi is thought to have originated in northern India during the 16th century Mughal Empire. Traditional desserts in that area already included condensed milk, and the Mughals added pistachios and saffron for flavoring and then froze the mixture in metal cones using a combination of ice and salt, giving rise to the kulfi dessert served today. Kulfi is popular not only in India but in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan and the Middle East as well. The dish can also be found in many Indian restaurants around the world.

Different flavors of Italian gelato. arsheffield. CC BY-NC 2.0

4. Gelato, Italy

Gelato is an Italian delicacy which differs from traditional American ice cream in its silky, creamy texture, as well as being denser. Gelato and American ice cream both contain milk and cream, but authentic gelato uses more milk than cream and does not usually contain egg yolks, which are a common ingredient in many ice creams. Gelato typically contains less butterfat as well, which makes the flavors more intense. It is also served at a temperature 10-15 degrees warmer than ice cream, so it melts more easily in one’s mouth. Modern gelato dates back to the Renaissance when Cosimo Rugierri, an alchemist, created a dessert from fruit, sugar and ice that delighted the powerful Medici family in Florence. Other accounts of modern gelato credit architect Bernardo Buontalenti, who is said to have prepared an ice cream dish from milk, egg yolks, wine, fruit and honey and served it to King Charles V of Spain. Whatever its origins, gelato quickly spread out of Italy, becoming a delicacy in other countries as well. Until 1686, however, gelato was mainly served in private residences of the wealthy, as ice and salt were expensive. Then, Italian Francesco Procopio Cutò opened a cafe in Paris where he sold gelato to the public. Since then, gelato has become a wildly popular treat that can be found on nearly every street in Italy and in restaurants and shops around the world.

5. Helado de paila, Ecuador

Helado de paila, literally “ice cream from a pot,” is a sorbet-like treat from Ibarra, Ecuador. The story goes that, 122 years ago in Ibarra, a teenage girl named Rosalía Suárez had nothing to give her friend as a 15th birthday gift. So, she decided to make her a dessert. Rosalía and a friend put natural fruit juice in a container and placed it on a wooden tray, where the container was surrounded by ice and straw to preserve it. They began to spin the container and beat the fruit juice, which turned into a form of ice cream. Rosalía perfected her recipe by adding sugar to the fruit juice and salt to the ice and began to sell her ice creams. Today, helados de paila are prepared in a way very similar to the technique that Rosalía Suárez first used. A blend of fruit and sugar is poured into a wooden bowl sitting in a larger bowl, or paila, which is already prepared with a layer of straw and a layer of ice and salt. The fruit mixture is stirred and eventually cools into the creamy helado de paila. Popular flavors include strawberry, blackberry, coconut, tree tomato and passionfruit.

Spaghettieis is made to look like a bowl of spaghetti. Joshua Shapiro. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

6. Spaghettieis, Germany

This popular German sundae is made from vanilla gelato, strawberry sauce and white chocolate shavings. The dish sounds innocuous enough, but what makes this treat unique is its presentation: the sundae is made to look just like a bowl of spaghetti. Spaghettieis was invented in 1969 by Dario Fontanella, whose father had moved from Northern Italy to Mannheim, Germany, in the 1930s. In an attempt to honor his Italian roots at the German ice cream parlor his family owned, Fontanella decided to create a bowl of spaghetti entirely from ice cream. Spaghettieis is made by putting vanilla gelato through a chilled spaetzle press (a machine to make German egg noodles) to achieve the spaghetti-noodle shape. The gelato is then topped with strawberry sauce to mimic tomato sauce, and shaved white chocolate curls to mimic parmesan. Apparently, when spaghettieis first began being served at ice cream parlors, it made children cry in disappointment that they were being served pasta rather than a dessert. Despite its tearful start, the dessert is widely popular today. Fontanella never patented his creation, so a variation of spaghettieis is served at nearly every ice cream parlor in Germany.

7. Akutaq, Alaska

Named after the Inupiaq word for “to stir,” Akutaq is an Indigenous Alaskan treat made by mixing fat, oil, berries and sometimes water or fresh snow together into a sweet dessert with a whipped texture. While berry-based akutaq is more similar to an American sorbet, there are also meat-based akutaqs in which the fat and oil are mixed with ground caribou or dried fish to create a more salty, gamey and savory dish. Traditionally in indigenous communities, the dish was made by women after the first catch of a polar bear or seal, and shared with members of the community. Akutaq varies by region depending on what types of flora and fauna are available to add. Indigenous people near the Alaskan coast used saltwater fish, while those inland used freshwater fish, and those in the north used bigger game like caribou, bear and musk-ox. Indigenous Alaskans have been making akutaq for thousands of years. Up until the 20th century, indigenous Alaskans held akutaq cooking contests during annual trade fairs, where members of various communities would compete to create new flavors. While akutaq can still be found today, in modern recipes the traditional caribou fat and seal oil are often replaced with Crisco and olive oil.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

A Glimpse into Oaxaca City’s Guelaguetza Festival

The annual Guelaguetza festival is one of the largest Indigenous celebrations in Mexico, preserving Oaxaca culture and tradition.

Women performing at the Guelaguetza Festival. Jen Wilton. CC BY 2.0

Oaxaca City’s Guelaguetza festival is a celebration of community and strength that occurs annually on the two Mondays after July 16. Also referred to as “Los Lunes del Cerro,” the festival has been a longstanding tradition in Oaxaca culture that predates Spanish colonization of the land in the 16th century. Although the cultural significance of the festival has shifted over the years, its core value of unity remains deeply rooted in the celebrations.

Prior to Spanish invasion, the festival had close ties to the religious celebration of the goddess of maize Centéotl in order to ensure a successful harvest season. While Centéotl still has a place in modern Guelaguetza celebrations, after Spanish colonization, festivities began to integrate Christian elements such as the feast day Our Lady of Mount Carmel which occurs on July 16.

The term “Guelaguetza” means “reciprocal exchanges of gifts and services” in the Zapotec language, which is the overarching structure of the festival. Historically, during Oaxacan celebrations, those attending would each bring some sort of item that was needed for the celebration such as food or supplies. These “guelaguetza” allowed the celebration to exist and exemplified the value of collaboration.

During the Guelaguetza festival in particular, inhabitants of Oaxaca’s eight regions unite, bringing their own unique traditions and knowledge to share with the larger community.

A couple dancing at the Guelaguetza Festival. Larry Lamsa. CC BY 2.0

Particularly, an exchange of culture occurs through song, dance and clothing. Individuals from each of the eight regions spend months prior to the festival perfecting song and dance routines to perform for the festival's attendees. After performing the number in their region's traditional clothing, they toss significant cultural items into the crowd. This exchange allows Oaxaca’s sub-cultures to not only exist but to thrive.

In addition to culture, there are plenty of other exchanges that occur during the festival, such as sharing traditional food that is prepared by inhabitants of each region and selling artisanal crafts in the city center.

The Guelaguetza festival has been traditionally celebrated on Cerro del Fortín, or Fortin Hill, in Oaxaca. In the 1970s an amphitheater was built specifically for the celebration. Seating 11,000 people, the amphitheater was built directly into a hill so that those looking down at the stage are able to clearly view the city below.

Oaxaca is home to sixteen different Indigenous groups in addition to its eight regions, so there is a vast array of cultures within the larger Oaxaca culture. Annual Guelaguetza celebrations have preserved these cultures over the years despite colonization and increasing tourism in the region, ensuring that Oaxacan traditions and stories will be preserved for coming generations.

Zara Irshad

A man in a Zoot Suit. ANGELOUX. CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Pachuco: A Short History of a Timeless Style

Mexican and Mexican American “Pachuco” culture formed in the late 19th century along the the US-Mexico border. Zoot suits and lowriding cars are popular symbols, but the unique look singled out Pachucos as targets of racial discrimination, such as the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles in 1943.

Read MoreVIDEO: The Sounds of Kenya

Kenya, located in East Africa, is home to a diverse collection of tribes, cultures, and religions that all intermingle to create the country that over 52 million people call home. While it has undergone development in the late 20th and 21st century, it still has vast swathes of untouched land that is as varied as the people that live on it. This video gives viewers a glimpse of the many different people, places, and landmarks in Kenya, with a focus on the daily joy that residents experience and share with those close to them. While the Kenyans appearing in the video may be from different tribes, they all share the same appreciation for their community and the land that surrounds them.

Amazing Styles of African Architecture

Africa is home to many beautiful styles of architecture, each shaped by the region and time when it developed.

The Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali. UN Mission in Mali. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While most people are familiar with European styles of architecture, such as Gothic and Renaissance, African architecture is not as frequently showcased. Other than the Pyramids at Giza, Africa’s architectural marvels are relatively little-known. International media often overlooks the cultural, historical and societal diversity of Africa in favor of news that portrays the continent in a negative light. There are a wide variety of architectural styles across Africa, each influenced by their environment and the time when they developed. Below are just three examples of Africa’s many unique architectural styles: Sudano-Sahelian, Afro-Modernist and Swahili.

The Larabanga Mosque in Larabanga, Ghana, built in the Sudano-Sahelian style. Carsten ten Brink. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

1. Sudano-Sahelian

Sudano-Sahelian architecture is characterized by the use of adobe, mud bricks and wooden-log support beams that jut out of the walls, as well as grassy materials like thatch and reeds which are used for roofing, reinforcement and insulation. The name Sudano-Sahelian refers to the indigenous peoples of the Sahel region in Africa—which extends from modern-day Senegal on the West Coast to Eritrea on the East Coast—and the Sudanian Savanna, just south of the Sahel. The Sudano-Sahel region is semi-arid, with an environment that transitions from the Saraha in the north to tropical deciduous forests in the south; there are both trees and wide, grassy plateaus. The earth is a major building resource in the region, which led to the development of the area’s distinct adobe architecture around 250 B.C. Today, ancient Sudano-Sahelian architecture remains a major influence on many contemporary African architects, such as Francis Kéré, who wants to showcase African traditions in his architectural projects.

The courtyard of The Great Mosque at Djenné. Johannes Zielcke. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

One of the most impressive examples of Sudano-Sahelian architecture is The Great Mosque of Djenné in Djenné, Mali. While the mosque was constructed in 1907, there have been a number of mosques on this same site since the 13th century, all built in the traditional Sudano-Sahelian style.

Ghana’s Independence Square. CC Chapman. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

2. Afro-Modernism

Afro-Modernism refers to Africa’s post-colonial experimental architecture boom of the 1960s and 1970s. Thirty-two African nations declared their independence from European colonial powers between 1957 and 1966. New elected governments ushered in an era of public works projects, including university campuses, banks, hotels and even ceremonial spaces like Ghana’s Independence Square. The architecture of the era largely used concrete, as it was more easily cooled than other materials—a necessity in hot, equatorial climates. Afro-Modernism draws on European styles of architecture; many buildings were designed by European architects. African influence is clearly present as well, though, and African architects like Samuel Opare Larbi were crucial to the movement. Staples of Afro-Modernism include bold shapes and the combination of traditional building materials like adobe with modern materials, such as concrete and steel.

Some examples of Afro-Modernism include the Kenyatta International Conference Centre in Nairobi, Kenya which has a lily-shaped auditorium; the FIDAK exhibition center in Dakar, Senegal, which is made up of a number of triangular prisms; and some buildings at the University of Zambia in Lusaka, Zambia, which has various open-air galleries and exposed staircases.

Lamu Old Town in Lamu, Kenya. These stone buildings are made in the Swahili style of architecture. Erik (HASH) Hersman. CC BY 2.0

3. Swahili

Monumental stone structures dating back to at least the 13th century populate the Swahili Coast, an 1,800-mile stretch along the Indian Ocean in modern-day Tanzania and Kenya. The area is rich with coral limestone, which became a crucial building material for the indigenous Swahili people.

A close-up of Swahili woodwork. Konstantinos Dafalias. CC BY 2.0

The stone architecture evolved over time to include intricate decorative elements, such as carved door frames and windows with natural and geometric designs. The carvings in Swahili architecture date back to the 17th century, with the earliest known example being from 1694. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the practice of stone and wood carving grew more widespread. Carvers drew influence from architecture and art overseas, including neo-Gothic, British Raj and Indian Gujarati styles.

A carved stone door in Lamu, Kenya. Justin Clements. CC BY 2.0

A tower in Stone Town on Unguja Island in the Tanzanian archipelago of Zanzibar. Frans Peeters. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Kenya’s Lamu Old Town is the oldest and most well-preserved Swahili settlement on the Swahili Coast. Lamu Old Town is constructed from coral limestone and mangrove timber and has been continuously inhabited for over 700 years. The Stone Town of Zanzibar, on Unguja Island, is another excellent example of Swahili architecture, especially the blending of African, Arabian, Indian and European influences. Both of these towns have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Sudano-Sahelian, Afro-Modernist and Swahili architecture are only three of Africa’s wide variety of architectural styles. Others include Somali, Afro-Federal, Nigerian and Ethiopian. For more stunning pictures of African architecture, visit this Twitter thread.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

8 Independence Days Around the World

The U.S. is not the only country that celebrates freedom from colonial rule. These eight countries have their own vibrant traditions to commemorate their independence days.

Women at an Independence Day parade in Jakarta, Indonesia. World Resources Institute. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Fourth of July is celebrated with parades, cookouts, fireworks displays and red-white-and-blue decorations as a way to commemorate the 1776 signing of the Declaration of Independence, which declared independence from British colonial rule. Although most people in the U.S. know the story of the Revolutionary War and the fight for independence, the U.S. is far from the only nation to struggle for autonomy under colonialism. Colonialism, typically perpetrated by large European powers like the British, Spanish and Portuguese empires, continued long after the U.S. won its independence. Many of the countries on the list below did not receive freedom from their colonial rulers until the end of World War II. Like the U.S., these eight countries each have their own traditions to honor their journey to independence.

When reading about independence, it is important to note that colonialism is not just a thing of the past; he UN reports that nearly 2 million people still live under colonialism in the 21st century. It is important that world media continue to advocate for political equality and self-government.

The church in Dolores Hidalgo, Mexico, where Father Hidalgo gave his cry for independence. Alfredo Carrillo. CC BY 2.0

1. Mexico

Contrary to common belief, Cinco de Mayo is not Mexico’s independence day. Cinco de Mayo commemorates Mexico’s victory over France in the May 5, 1862 Battle of Puebla during the Franco-Mexican War. Mexico’s independence day falls on September 16 and celebrates the country’s liberation from Spain, which ruled Mexico as a colony for over 300 years. The day marks the anniversary of “El Grito de Dolores” (The Cry of Dolores), a rallying speech made in 1810 by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest advocating for revolution. It is said that on the night of September 16, 1810, Father Hidalgo rang the church bell in the town of Dolores and urged the assembled villagers to revolt. He then took up the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico. Father Hidalgo’s cry began the Mexican War of Independence, a bloody fight which raged until August 24, 1821, when Spain officially withdrew and recognized Mexico as an independent country.

Today, Father Hidalgo is known as the Father of Mexican Independence; each year on September 16, his rallying cry is celebrated with fireworks, parades and live music. Also, the president of Mexico reenacts “El Grito” by ringing the church bell of Dolores and reciting the speech made by Father Hidalgo over two hundred years ago. The event draws massive crowds eager to honor Mexico’s fight for independence.

2. South Korea

Korea’s National Liberation Day, or “Gwangbokjeol”, is celebrated in both South and North Korea annually on August 15, the date of the official establishment of the Republic of Korea. Korea struggled under Japanese imperial rule for 35 years until the end of World War II in 1945. Beginning in 1910, Korea was a Japanese colony. Korea’s social, political and economic policies were controlled by Japan, and many Koreans faced forced assimilation into Japanese culture, such as being made to take Japanese names. During Japan’s occupation, there were many movements that attempted to gain independence for Korean. The most notable of these began on March 1, 1919, when a group of Korean nationalists started a series of demonstrations calling for Korean independence. The demonstrations continued for a year and approximately 2 million people participated in over 1,500 demonstrations before they were quashed by Japanese forces. Despite continuous efforts from Korean independence groups, the country did not earn its independence until August 15, 1945. Exactly three years later, on August 15, 1948, the Republic of Korea was established. South Korea also celebrates Foundation Day, which falls on October 3 each year. It commemorates the foundation of Gojoseon, the first Korean kingdom, in 2333 B.C.

The South Korean flag is flown across the country on National Liberation Day, from streetlights and outside public buildings to private residences. The South Korean government holds an official celebration, and the day even has an official song. On National Liberation Day, the descendants of independence activists can ride public transport and visit museums for free, and the government can grant special pardons to prisoners. National Liberation Day is occasionally celebrated with fireworks, but South Korea’s larger fireworks displays are reserved for Foundation Day.

The independence monument in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Ethan Crowley. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

3. Cambodia

Full Cambodian independence came on November 9, 1953, when France officially gave up control of the region. The region that is now Cambodia became part of the French protectorate of Indochina in 1863 and remained under French influence for nearly a century. In 1941, France installed Norodom Sihanouk, from Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on the throne. As King under the French protectorate, Sihanouk had little power; France was still the main force controlling Cambodia. However, toward the end of World War II in March 1945, Sihanouk declared Cambodia’s independence after realizing, similarly as had the South Koreans with Japan, that France’s involvement in the war had left it weaker in the colony. When the war ended, France regained military control of the region, but Sihanouk’s declaration had ignited a push for independence within Cambodia. In 1953, France finally agreed to recognize Cambodia as an independent state with Sihanouk as its leader. The French military finally withdrew in 1954, and Sihanouk founded the People’s Socialist Community in 1955. Sihanouk remained involved in Cambodian politics for years, serving as prime minister, foreign minister, UN representative and later as King again.

Each year on November 9, people flock to Phnom Penh to gather around the independence monument. Members of the Cambodian government, including the monarch, assemble at the monument as well and speeches are made. The gathering is followed by a colorful parade outside the Royal Palace, complete with floats and live music from marching bands. At night, the Royal Palace and many other buildings are brilliantly lit up and there is a large fireworks display.

A statue of liberty in Bolivia, with signs made to celebrate independence day. Dan Lundberg. CC BY-SA 2.0

4. Bolivia

Bolivian independence took more than 15 years to achieve, but it finally occurred on August 6, 1825, after centuries of Spanish control. What is now Bolivia was known as Charcas or Upper Peru, as it was part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru. The Viceroyalty of Peru was established in 1543 during the beginnings of Spain’s exploration of the New World,, and included nearly all of South America. Bolivia was a particularly lucrative part of the viceroyalty, as its silver mines were the Spanish Empire’s main source of revenue. Most of the mines were staffed by Bolivian natives who were extorted for labor by the Spanish Empire—the workers were ill-treated and ill-compensated, which began to sow seeds of dissent against the Spanish. In 1776, Bolivia became part of the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, still under Spanish control. It was not until 1809, when Napoleon attacked Spain, that Bolivia’s independence movements were able to truly begin. Taking advantage of Spain’s focus on the home-front, Simon Bolivar and Antonio Jose de Sucre led Bolivian nationalists in a campaign for Bolivian independence. After years of fighting, on August 6, 1825, Bolivia’s Declaration of Independence was signed.

August 6 is celebrated as a national holiday known as “Dia de la Patria.” Throughout the country there are parades, gun salutes, street dances and carnivals, as well as events memorializing the nation’s history.

5. India

India celebrates its independence from British rule on August 15. On this day in 1947, after over 200 years of British colonial rule, India officially gained independence. August 15, 1947 also marks the day that the Indian subcontinent was partitioned into two countries: India and Pakistan. Britain assumed control of India in 1757 through the British East India Company. 100 years later, in 1857, the first significant push towards Indian independence occurred during the Indian Mutiny, or the Revolt of 1857. While the revolt was ultimately unsuccessful, it did lead to a transfer of power from the trading company to the British government, but it also sparked continued protests against Britain’s exploitation of India. During World War I , the Indian independence movement grew, led by Mahatma Gandhi and political organizations like the Indian National Congress. In 1947, India finally became an independent nation. Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of the newly independent India, and during a speech at the Red Fort of Delhi, he hoisted an Indian National flag high above the Lahori Gate.

In homage to this moment, India’s prime minister delivers a speech at the Red Fort of Delhi each year on August 15. State capitals host flag hoisting ceremonies and cultural programs, and buildings are decorated with the flag and strings of lights. In north and central India, the day’s main festivity is kite flying, as Indian revolutionaries used to fly kites with slogans protesting British rule.

A flag march during Costa Rica’s Independence Day celebrations. Bruce Thomson. CC BY 2.0

6. Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s journey to independence is a bit different from the other countries on this list. Central America is one of the few areas where there was no large-scale fight for independence. On the heels of its defeat by Mexico, Spain realized that keeping colonies in the region was no longer lucrative. On September 15, 1821, a Central American congress signed “The Act of Independence” declaring Central America’s independence from Spain. Although the declaration was signed in September, news of their newfound independence didn’t reach Costa Rica until nearly a month later—on October 13, 1821—because the message was carried on horseback from Guatemala.

To celebrate the anniversary of their independence, Costa Ricans throw large parades each September 15. The festivities stretch beyond just one day, though. Starting days prior to the main celebration, an Independence Torch is lit and carried by a series of runners from Guatemala to Cartago, Costa Rica’s colonial capital, by September 14, as a way to commemorate the news of independence traveling the same route. School children spend the days leading up to independence making and decorating faroles, or lanterns, and parade through the streets with them on the night of September 14.

Thousands of people gather to celebrate Brazil’s independence. Ptangokilo. CC BY-NC 2.0

7. Brazil

Brazil officially became its own nation on September 22, 1822, after almost 300 years of Portuguese colonial rule. However, Brazil celebrates its independence day on September 7, the anniversary of Portuguese Regent Prince Dom Pedro’s declaration of Brazil’s independence. The Portuguese Empire colonized Brazil in the 16th century, and it was not until the early 1800s that Brazil began to find success in its push for independence. When Napoleon invaded Portugal in 1807, the Portuguese royal family fled to Brazil. The Portuguese Court remained in Brazil until 1820 when a revolution in Portugal forced the King to return. Since Brazil was then a kingdom, the King’s son, Prince Dom Pedro, remained in Brazil as its ruler. In 1822, the King issued a court order recalling Dom Pedro back to Portugal, but the Prince instead declared his allegiance with Brazil and remained there, calling for freedom from Portuguese rule. Dom Pedro became the first emperor of the independent Brazil.

On September 7, Brazilians around the world celebrate Brazil’s independence. In Brazil, there are parades, concerts, fireworks and air shows. The largest celebration takes place in the capital, Brasilia, and is attended by the President of the Republic along with around fifty-thousand other people.

8. Indonesia

Independence day in Indonesia falls on August 17, the day its Declaration of Independence was signed in 1945. The Declaration freed Indonesia, then known as the Dutch East Indies, from oppressive Dutch colonial rule under which Indonesians were forced into labor and exploited. The Dutch actually lost control of the colony in 1942 when Japan invaded Indonesia and took over. After Japan surrendered at the end of WWII on August 17, 1945, Indonesian nationalists seized their opportunity to declare independence before the area was once again occupied by the Dutch. The Dutch government refused to recognize this independence, launching two major military campaigns between 1947 and 1948 to reclaim control. Indonesiansheld their ground and Indonesia received support from the U.N. and the U.S. In December of 1949, the Dutch finally released their hold and recognized the independence of Indonesia.

Like in India, Indonesia’s independence day is celebrated each year with a flag-raising ceremony at the National Palace. The fun celebrations, however, are organized by local neighborhoods. Across the country, people take part in traditional games and contests. One of the most popular is panjat pinang, where a palm trunk is erected in a public area and greased with a mixture of clay and oil. The goal is simple: make it to the top to win the prize hung there. Other traditions include races, cooking contests and krupuk eating contests.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

A tunnelbana train in Stockholm. Tony Webster. CC BY 2.0.

10 Metro Systems Around the World to Ride in Your Lifetime

Metro systems exist on every inhabited continent on the planet, being as unique in comparison to one another as are the diverse cultures and communities they serve. Some are highly efficient at moving people from point A to point B, others are rooted in the history of the local community and a few even serve as living art galleries that are ever-expanding. Here is our guide to the 10 must-visit metro systems to ride on in your lifetime.

1. Tunnelbana, Stockholm, Sweden

Serving 100 stations throughout the region, Stockholm’s Tunnelbana, which translates to “tunnel railroad,” is one of the newer metro systems in Europe, opening its first line in 1950. What makes the Tunnelbana unique is that it is considered to be the world’s longest art gallery, featuring an extensive collection of art made by over 150 artists.

2. Buenos Aires Underground, Argentina

The Buenos Aires Underground, known locally as Subte, is the oldest underground railway system in the Southern Hemisphere, dating back to 1913. The system hones in on its historic origins by providing both historic and modern train cars and stations which are spread out across its seven lines.

3. Seoul Metropolitan Subway, South Korea

Featuring 22 lines spread across 728 stations that serve both the heart of the city and rural communities, the Seoul Metropolitan Subway is one of the longest systems in the world. Opening its doors in 1974, Seoul's subway continues to grow, with several line extensions slated to open throughout the decade.

The iconic London Underground sign in front of Big Ben. Defence Images. CC BY-NC 2.0.

4. London Underground, UK

The oldest underground railway in the world, the London Underground began operation in 1863 and has since grown to serve 270 stations. Known in London as “the Tube,” the metro system provides easy access to neighborhoods throughout Central and Greater London, as well as connections to a slew of airports and other transit systems.

A Berlin U-Bahn train in a station. Michael Day. CC BY 2.0.

5. Berlin U-Bahn, Germany

Famous for its eye-catching yellow trains, the Berlin U-Bahn is one of the oldest and largest metro systems in Europe. The system had been partly severed in two parts during the Cold War due to the divide between East and West Berlin. Today it boasts 10 lines serving 173 stations, with an annual ridership of around 553.1 million.